This report was commissioned by LGBT+ Consortium as part of its National Emergencies Partnership funded programme. It’s about why bi organisations currently get so little “LGBT” funding, and how the obstacles could be addressed.

It was produced by three bi community organisers in the UK, based primarily on experiences of fellow organisers. Researchers were Jennifer Moore, Libby Baxter-Williams and John G, in May and June 2021. Thanks to everyone who gave their time to speak to us!

We expect its audience to be

-

potential funders seeking to reach bi communities

-

people who consider themselves part of bi communities, and

-

people interested in funding in general, especially of grass-roots groups.

If you’re planning to put the recommendations into practice, you’ll probably want to consult the full report, with more history, more detail, more references, and more quotes from bi people.

-

On average as a demographic, bi people fare as badly as, or worse than, lesbian & gay people on many outcomes. Bisexuality is stigmatised and ignored.

-

Nominally “LGBT” projects or spaces aren’t necessarily doing anything for the “B”.

-

Bi spaces can be very important to people for various reasons: feeling understood, freedom from anti-bi prejudice, etc.

-

Almost all current UK bi spaces are run by unpaid volunteers in limited amounts of “spare” time. Many areas have no bi group at all.

-

UK bi communities have a long tradition of “creatively making do” – but could accomplish much more with adequate funding. Key areas include outreach and access.

-

We recommend:

-

ring-fencing a percentage of “LGBT” funding in proportion to the percentage of bi people, with half or more under the direct control of a bi panel.

-

creating a “virtual bi centre“, where one or more workers is embedded within a larger organisation, to provide practical support for grassroots groups and cross-group projects.

-

hiring bi organisers to reach, train and support bi organisers.

-

adapting funding methods for grassroots groups to be simpler, less formal, and less of a gamble, especially where amounts are small.

-

making basic group-running resources available to volunteer organisers on request, such as books, printed flyers, or support with online calendar updating.

-

where nominally “LGBT” organisations apply for funding, making it conditional on whether they can demonstrate genuinely serving the “B”.

1.1 Bisexuality background

It’s possible that around 5% to 10% of the UK population, or more, has experienced some attractions not limited to “gay” or “straight”. But they don’t necessarily call themselves “bisexual”.

In day to day life, some may not use a sexuality “label” at all; some may prefer other descriptions such as “queer” or “pan”.

In this report, for simplicity we’ll say “bi”. Or sometimes, to emphasise the variety of chosen labels, we’ll say “under the bi umbrella”.

A common myth is that bi people “have it easier” than lesbians and gay men, because we’re “only half gay”, and “can pass as straight”. However, being invisible and stigmatised isn’t a healthy position. On many measures of mental and physical health, bi people on average do worse than either straight or gay people.

Bi organisers were part of the gay liberation movement in the 1970s. In the 1980s, the political climate shifted, making bi people less welcome in gay spaces and especially in lesbian spaces. Prejudice against bi people is still common within both mainstream culture and gay communities.

As a result, groups which are nominally for LGBT people (Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans) are not necessarily supportive to bi people in reality.

Typical elements of anti-bi prejudice include “confused”, “greedy” and “unreliable”. It’s also common simply to ignore or deny the existence of bi people; this is sometimes called “bi erasure“.

Many bi people find bi-majority space to be supportive to their wellbeing. Bi spaces typically avoid gatekeeping “who’s bi enough” or who uses which label. Most bi social spaces actively welcome non-bi partners or friends.

1.2 UK bi communities in 2021

What resources exist specifically for bi people in the UK in 2021 are almost entirely volunteer-run.

There are currently two UK bi charities: Bi Pride and BiCon Continuity. Each is linked to an annual event, and currently run entirely by volunteers.

The Scottish Bi+ Network is the main bi organisation in Scotland, and currently has a year’s funding for a part-time admin worker.

The majority of local groups which gave input to our survey had no bank account, and run “on a shoe-string“. We estimate that there may be around 60 to 70 small groups of this type across the country.

There are a handful of local/regional groups or events which have got as far as having a bank account: for example, Brum Bi Group or London BiFest.

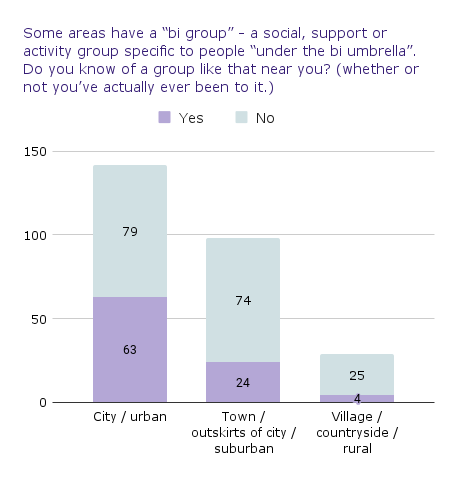

In our convenience sample of 280-odd bi people, mostly based in urban and suburban areas, about two-thirds didn’t know of a local bi group near them.

Bi people of colour (PoC) may prefer to lead or participate in groups for LGBT people of colour, rather than in a white-led, white-majority bi scene. Therefore, reaching bi people of colour means thinking about those groups too.

We estimate that between 120 and 160 people are currently involved in organising bi-majority spaces. Almost all are white; many are disabled.

Most of the smaller groups or events have never applied for grant funding. We asked why not; the most common reason was the lack of any expectation of getting it, combined with limited time and energy.

Although things are beginning to change, the UK out-bi community has a long tradition of “creatively making things work on a shoe-string”, and dipping into its own pockets, informally or via more structured crowd-funding.

2. Key obstacles “in between” bi people and existing funding

The context for this research is that the LGBT Consortium had identified a gap:

Despite active attempts to make the funding more accessible to bi orgs, uptake was still low … we need and must do more to ensure bi organisations have access to vital LGBT+ funds when they are available … .

We describe three key obstacles which currently hinder grant money from reaching bi people.

-

The first factor is a historical lack of ring-fencing for specifically bi needs and projects. This links with a key unreliable assumption from funders: the idea that money reaching “LGB”/”LGBT” groups is already being used to support bi people.

-

The second obstacle is the expectation that bi organisations will slot neatly into funding structures which already exist. For example, funders may wrongly assume that volunteers have spare time to devote to grant applications.

-

The third obstacle is the lack of a track record of funders actually giving money to bi organisations. It’s been a rational choice for bi organisers not to gamble their limited time on such poor odds. However, this factor could change quickly, if funders change the landscape of structural obstacles, and money starts to become genuinely available.

As part of our research remit, we were to suggest

What funders, particularly Consortium, can put in place to ensure there is fair and equal access to future grant funds.

The following recommendations are our and our interviewees’ responses to that question, and to the structural obstacles we’ve identified.

-

Allocate a fair percentage of LGBT money to be channelled to bi people, then figure out how to get it there.

We suggest that if B% is the percentage of bi people within an LGBT community, at least half of B% of “LGBT” money should go to projects run primarily by bi people, and approved by a bi panel, with a further quarter of B% ring-fenced for bi‑specific projects run by other groups.

-

Fund, and help to organise, a Virtual Bi Centre, where one or more workers is technically employed by an organisation such as the Consortium, while answerable in practice to bi leadership.

The initial focus of the Virtual Bi Centre would be development and admin work to support grass-roots bi groups, local events and national initiatives which run year-round.

-

Support and fund the creation of a panel to make decisions about the half-of-£B bi‑specific money.

Either the same panel, or a similar one, could make big-picture decisions about worker time at the Virtual Bi Centre, although the day-to-day supervision of the worker(s) wouldn’t fall upon this group.

-

In the meantime and in general, find ways to support grass-roots groups and volunteer organisers which don’t rely on them having spare time or energy to navigate your systems.

For example, use informal methods for small sums, don’t insist that small groups have a bank account, and make as transparent as possible what the chances are of actually getting the money.

-

Where you require detail as part of an application, think ahead to the kind of research which applicants will likely need to do. Provide some of it as a “starter framework“, rather than making each applicant start from scratch.

For example, suggest estimates for costs, or give statistics you’ve already accepted for demonstrating need.

-

Prioritise supporting spaces centred on LGBT/queer groups for people of colour, especially (where they exist) spaces for bi people of colour.

-

Hire bi organisers to reach and support bi organisers.

-

Support and/or offer fully-funded training tailored to the needs of bi organisers. This would include how to run groups, how to run campaigns, and how to understand the funding landscape.

To design the curriculum, hire experienced bi organisers, who know what has and hasn’t been useful to them in the past.

-

Whenever assessing funding applications for nominally LGB or LGBT projects, score the application partly on how they’re serving their bi participants.

(This applies across the board, not only for money ring-fenced for bi communities. But make an exception if the application is for a project specific to the L or the G, with no implied claim that it was meant to include bi people.)

-

Some guidelines on general approach:

-

Assume that every space includes bi people. Often it’ll be true. Mainstream culture is bad at noticing us.

-

If you want bi people to feel welcome, welcome us, and show some familiarity with our world. Don’t assume that a generic “LGB” welcome will reassure bi people that it’s safe to come out.

-

When you want to reach behaviourally bisexual people, assume you’ll need to use mainstream media – not only “gay” media or even “bi” media.

-

If you’re familiar with a “gay scene“: don’t rely on a mental model of that, in order to map what might be happening in a corresponding “bi scene“.

-

Recognise the value of people who can do a beautiful job of outreach, welcoming people and holding a space, even if they’re no good at admin. Ensure they have everything they need, to do what they wanted to do in the first place.

In the rest of our report, we use case studies and quotes to give more of a picture of the current landscape, and give a few suggestions for how our recommendations might be implemented.

4.1 Why bi spaces are important, even when LGB/LGBT spaces exist

In a short survey open to anyone “under the bi umbrella”, we invited people to comment on anything related to groups they go to.

(Each arrow represents the start of a different person’s comment. Bold text is added for ease of picking out themes.)

Some people spoke of what bi spaces gave them:

→ I would love to go to more exclusively bi events, as I have been to one where we discussed bi literature, and I felt tremendously enriched by this experience. You don’t always notice how bi experiences and deep discussions are sidelined until you are in a bi space.

→ Bi Cardiff has been a lifeline to me as someone who came out later in life (in my 40s). Just to be able to meet and chat with other bi people, share experiences, and ask about places to go for support (eg with mental health issues related to my orientation) has been so important.

→ I think that bi organisations are really important to provide spaces where we can feel understood, and not afraid of the myths and ignorance that’s present even among generally open-minded people and spaces.

Some commented on troubles or awkwardness they’d experienced in so‑called LGBT spaces:

→ Unless they’re run by bi people, in my experience, LGBT+ groups are always bi erasing and/or actively biphobic. I often feel more comfortable being out as a bi person in predominantly hetero social spaces than in predominantly gay spaces.

→ There are local LGBTQ+ groups, but there are always a few people not v welcoming of bi people

Several contributors compared experiences they’d had in different spaces:

→ I feel more comfortable in groups that are labelled as explicitly Bi or Bi-inclusive or Bi-led. I feel more included but still nervous in certain explicitly queer or queer-led spaces where I worry about not being “gay enough” for them. In spaces that aren’t labelled at all but claim to be inclusive, I still worry about people making assumptions or being biphobic.

Not everyone felt the need of a bi‑specific group:

→ Being bi is not a major part of my identity, being queer and a woman is.

Many people’s comments included wishes for more bi spaces to exist!

→ Just a note about how sorely needed bi spaces are, particularly the kind that don’t centre around drinking or dating

→ I would love a bi group (I’d actually love to have any queer group, everything I see is big city focused). The only LGBTQ+ things I’ve seen locally have been for under 24, and I’m very much not of that age group.

→ I wish there were more! I’m not aware of any bi groups near me despite living in the centre of a city

4.2 Where bi people go, other than bi groups

In our survey open to anyone “under the bi umbrella”, we invited people to mention a non-bi group they went to, if any. About 40% did. There was an enormous variety of groups.

-

Various LGBTQ groups, including work networks, parent/family support groups, Black Pride, campaigning groups or ones with a social/creative/sporting theme.

-

Choirs, musicals, drama, Gilbert & Sullivan, ballroom dancing, country dance.

-

Writing, including poetry groups and a NaNoWriMo writing meetup.

-

Book clubs, a film club, board games, Dungeons & Dragons.

-

Swimming, rowing, wrestling, boxing, walking.

-

Knitting, crochet, cosplay, Hackspace, “crafting and sharing craft knowledge”.

-

Other social/support groups with some connection to relationships or sexuality, such as polyamory, kink, asexuality.

-

Unions, campaign groups, mutual aid, anti-fascism.

4.3 What’s typical at a grass-roots bi group

A typical small grass-roots bi group would have one “main” organiser. The group would meet once a month in a pub, or, if they’re lucky, some kind of community centre.

Finding a venue to meet in is often one of the trickiest parts of organising. Often, the venue isn’t ideal for access in some way – but alternatives are either worse or too expensive.

Publicity happens primarily online without spending money. If the group needs money, e.g. for flyers or a subscription to Meetup.com, it comes either from the organiser’s pocket or from members.

Hosting skills vary, but it would be common for the organiser to offer to meet newcomers beforehand outside the venue, so you don’t have to walk in by yourself. Topics are usually random; there might be a bit of bi-related discussion, there might just be ordinary chat.

There are usually some “regulars” and some people who dip in more rarely. Sometimes, people only come a few times and that’s enough – they’ve got what they needed at that time.

The typical average group would be pretty white, but if at some point enough people of colour start coming regularly, it can stick that way.

If there’s a local Pride march, it’s very likely that group members will meet up and march together, perhaps with some bi and pan flags or even a home-made banner.

Often the group will do something special on or near 23 September, to mark International Celebrate Bisexuality Day, often better known as Bi Visibility Day.

Some people travel 15 or 20 miles to get to their nearest group. If you don’t know any bi people in the rest of your life, the group can feel like a vital haven.

During the covid pandemic, some groups switched to meeting online, typically using Zoom software. A few have been able to organise outdoor meetups such as picnics or walks.

Some groups have gradually built up membership through steady outreach, and eventually got to the level where they’re also doing other things. For example, the Brum bi group is currently thriving and runs “Bi Camp”. By this point, there’s usually more than one regular organiser, and they may decide it’s worth going to the bother of sorting out a bank account.

However, typically there’s no constitution, committee or bank account. That is, the group isn’t a legal entity at all, only an informal planned gathering of people.

When bigger bi events have happened, such as a one-day BiFest or annual BiCon, often the organisers of those have been branching out from earlier experience running a bi group like this.

5. Applying, or not applying, for funding

Of 22 bi organisers who responded to our written survey, 4 had at some point applied for funding. In a tick-box question, we asked the other 18 why they hadn’t.

The most common reasons chosen were as follows, most popular first:

-

Expecting not to get the money, hence waste of effort (1 in 2)

-

Don’t have time/energy

-

Would have to set up bank account

-

We could use £10, £50, £500, but they want you to apply for thousands

-

Group is going OK as it is – not ambitious to expand

-

Wouldn’t know where to look (1 in 3)

-

Wouldn’t know how to apply

-

Ongoing extra admin to report back to funders

We also offered “Never really thought about it” as an option, but only 3 people ticked that (1 in 6). Most people had thought about it.

Here we’ll look at some of the things people said about this area.

5.1 Time, energy, the admin burden, and getting nothing back

Making applications is time-consuming, especially if you haven’t already got any of the bits of info lined up from a previous one.

→ Beyond the very basic questions on application forms (that I’ve seen), every question seems to require something I can’t supply yet, or require significant research or creation/digging into records.

→ Our volunteers are mostly disabled people that can give a few hours a week, myself included.

→ [A lot of organisers are] doing a 9-to-5 job, and then, you know, running the bi group in a tiny moment on the side.

Bank accounts add another layer of tedious admin:

→ [Setting up the account] was hard work, and involved one of our former Trustees having to visit a branch in person more than once… Even once the account was opened, it took ages to add additional people as signatories to the account.

An application form might require you to get multiple quotes:

→ A thing that is exhausting about funding bids for small organisations is getting exact costings.

They are such small grants and they all require the same amount of time and input.

If you’re not ready when it comes along, you’ll miss out:

→ You need to be on the ball to apply for it. Once you’ve seen a specific fund, you need to already have your bank account and committee and referees, because the closing date will be in like a month.

Nevertheless, some groups did invest their volunteers’ time in making applications – often unsuccessfully.

→ Generic ‘thanks for your application’ email saying we’d been unsuccessful, no specific information given.

→ [We were told] that the fund was oversubscribed: £90,000 in applications for a £20,000 fund.

→ You put a lot of time into the application, then you get nothing.

The result was less enthusiasm for applying again, especially combined with the limited available time and energy.

→ We don’t have time to spend on what we felt were fruitless activities.

5.2 Misfitting with what’s on offer

There were various ways in which groups and events found themselves misfitting with how funding bodies wanted to operate.

A common one was wanting the wrong amount of money, when funders want to dole out £5,000 or £50,000.

→ Feels too formal a process for the small amount needed – but it would be great to take that burden of donating off attendees.

→ And we don’t want it to be “tiny amount or huge amounts“. Actually recognising that we might need something in between, and what shape that takes will depend on the project.

Dealing with middling-to-big amounts of money also means having middling-to-big amounts of time:

→ There were the odd times where we’ve said “actually, we could probably apply for big amounts of money. What would we do with that? We do not have the ability to look after that money.”

→ The money is the big problem, but actually the time really kind of sits with that.

Funders might not be receptive to new inventions:

→ They need to be far less “We didn’t expect you to ask for this, this is why we are not giving it to you”.

A classic way to misfit, which affects the whole voluntary sector, is when you need running costs / core costs, whereas funders want to pay for a one-off:

→ Also many places don’t fund running costs, they like a big project to put their name on.

→ My experience has been that people really like funding projects, but running costs not so much.

Funding applications can be much less flexible than real life:

→ We will spend differently depending on how much money we have, and we will change course depending on what we can deliver. What I would love is to be able to say that XYZ is our final goal but XY or YZ will get us part way there and we will scrap around for the rest.

It can feel impossible to get the initial money which would help you to get going and then get more.

→ One of the things I’ve been told is that any organisation’s first paid member of staff should be a fundraiser. And… I’m not a fundraiser. And I have no access therefore to get the funding to pay a fundraiser. So that goes round in a tiny circle.

→ If we had funding, and were able to pay people, then more would get done.

5.3 Not knowing where, not knowing how

This was less often talked about, but it did come up:

→ Not having the skills to apply, or the knowledge of the grants on offer is a big thing.

→ When I did a brief internship at the Fawcett Society, many, many years ago, I discovered they have a piece of software called “Raiser’s Edge”. It was a database of grant giving foundations. And so I’ve looked into that, and it’s £1,000 a year, or whatever it costs at the moment.

So there are lots and lots of smaller organisations, giving grants out, and we’re never ever gonna find out that that money’s available.

Rather than small groups trying to find out where the money is, it would help if sometimes the people with the money went looking for the good work:

→ If funders watched bi projects, and reached out to ask how money could help, and offered what was needed where they saw good work happening

5.4 Anti-bi prejudice in the sector

Part of the big picture is that the wider culture of prejudice against bi people also runs through charities and funding bodies at the management level. The B continues to be erased and neglected in those contexts too.

→ [Organisation] got a very substantial grant to do a ‘what’s available’ guide to one city. It says it has “hundreds of LGBTQ+ services” listed. Click on “Bi” and the single thing that appears on the map is labelled “Gay men’s walk-in clinic”.

→ LGBT organisations use statistics about bi trauma to get funding and donations for primarily LG or LGT social and health projects. They combine LG&B stats to prove that LGB people have worse mental health, are more likely to live in poverty, etc. therefore need targeted help – but they don’t mention that the group most affected is the bi community, and it certainly isn’t reflected in the services provided. They only include ‘bi’ in the name or with other insignificant token gestures.

→ Don’t just advertise events / spaces / projects in the ‘gay’ / ‘lesbian and gay’ / ‘LGBT’ media or scene. We know from research done on gay & bisexual men’s health that far fewer non-gay identified men look at those vs gay identified men.

5.5 Dipping into the community’s pockets

A very common solution to the funding obstacles has been to keep things small and dip into our own pockets.

Sometimes this was a typical ticketed event, albeit with no-one getting paid for organising. Sometimes it’s “pass the hat on the day” – though this can be financially risky for the organiser.

Sometimes it’s organisers who can afford to keep their lives simple by paying the group’s expenses from their own money. Two-thirds of organisers in our survey had resorted to this.

→ The actual subscription costs for the MeetUp group, I pay for that personally.

→ It was the beginning of last year, just before the pandemic, that my partner and I who co-run the group went leafleting [in town] – in the hope that people who aren’t that Internet focused would find the group. That came out of our own pocket.

After “From organisers’ own pocket”, the next most common survey result was “From the community: donations, subs, crowdfunding, pay what you want events”. Several organisers expressed unease at the ethical implications of that:

→ … feeding off ourselves, and as a community we are not that well off.

→ We’re quite poor as a community.

→ I’m sick of people asking me to do stuff for free. So I don’t wanna ask other people to do stuff for free, for me. And [for bi events] we’d try to keep cost to attend very low, as well. Which is difficult, because you don’t make money that way. But it’s important to me that we make events accessible, and pay people who are performing, so yeah.

→ [About the idea of being paid to do things] If it’s other bi people paying for it, then I feel bad.

5.6 The tradition of creatively “making do”

Several of our interviewees and contributors remembered back towards the roots of the present out-bi movement, beginning to organise together as bi people in the 1980s and 1990s (rather than invisibly contributing within Gay Liberation spaces).

The habit began then of creatively “making do” with little or no money:

→ Bi groups have always run on shoe-strings. Partly because [many of the groups] come from a background of being able to use free or low-cost non-alcohol venues.

We automatically first think, well how can we do this with what we’ve already got?

We automatically assume that we’re not going to get any funding, and we do that because we’ve never had any funding.

→ The DIY nature is a hallmark of the community, but also its downfall, basically.

→ It’s one of our greatest strengths and our greatest weaknesses.

Even though the tradition of creatively working out “how we can do this anyway” is still present, people in our research discussions were very ready to talk about paid work.

→ If you want to run big events, then you really need to be paying people. There’s a big difference between rocking up for a couple of hours once a month and basically running an organisation day in day out.

→ I would genuinely love to have a full-time job doing equality stuff.

There was some wariness about how that could be set up well, especially in situations when some people might be paid alongside others who weren’t.

→ Asking people to give their time voluntarily doesn’t sit right with us, and we think people should be paid. But figuring out the structure how to do that might be difficult.

→ In my experience the biggest problem comes when some people are paid and some people are not, and the criteria for that are either unclear or seen as unfair.

And yet, a doubt remained about whether we could be paid:

→ I feel that I could do enough [work for the community] that I wouldn’t feel bad for taking money. The question is who would be paying me. It’s not realistic, but it’s a nice idea.

To wrap up this section, two comments looking to the future:

→ I just want to say that a lot of the questions you ask, I never even thought about. Like “what would I do if I had somebody to work for a day” – what? But I think you could see as I was answering more and more, that the idea for what the potential is really grows the more you actually just ask the questions. And then you can expand on your idea and see the the potential of it. And I think that’s really valuable, that exercise.

→ We’ve seen how successful we can be running shoestring events, and shoestring organisations, which have, you know, decades of life, but no money. What could [an organisation] do if it was funded from the beginning?

QTIPoC Notts is for Queer, Trans and Intersex People of Colour (QTIPoC, often pronounced “cutie-pok”), in Nottingham and the surrounding areas. The quotes in this section are from an interview with Tuk, a bi woman who’s one of the group’s founders.

This group isn’t technically “a bi group”. However, the group has bi leadership and bi membership, and runs in ways very similar to a typical grass-roots bi group. Pretty much everything practical that Tuk describes about running the group, there’ll be bi group organisers across the UK nodding along as they read this. It illuminates beautifully the kind of limitations you bump into as volunteer organisers with very limited time.

I remember, our first meeting, we went round the table, it was maybe 10, 12 people? And we asked what people wanted from the group. And everybody but one person said, basically, that they need a space where it’s people of colour, because they’ve experienced racism from queer spaces. [They] had had specific experiences that made them want to make the group.

As with many grass-roots groups, the first money came from the organisers, group members and friends.

In the beginning, when we first set it up… we obviously didn’t have any money. I don’t think we needed money for a while, actually, until organising that event [a fundraiser in a small venue]. Because at that point, we still didn’t have any money of our own. So to organise the event, I think I put £100 in? And then we made… £150. [laughter]

Tuk still hadn’t paid herself back for that seed money.

Which I don’t mind. But now [in a different job], I can’t afford to put money in.

The group doesn’t have a bank account; what money they’ve had still goes via Tuk’s personal account.

We wanted to set up a bank account. It was because we wanted to apply for some funding, I can’t remember where from.

But then to have a bank account, we had to have a constitution. We talked about it. Nobody had the time to write a constitution.

None of us had experience in writing one. I think somebody offered to send us a constitution for their other group, that we could use as a template.

But we’re all volunteers, and we all are very busy. So we just do it the easy way, you know.

The group had put time into applying for funding, but unsuccessfully:

I applied for the Resourcing Racial Justice fund, and they had funds of… I think it was up to £50,000, but I only applied for the second-lowest one, just to cover future events. But we didn’t get it.

You either had to make an 8-minute video, or a, I think 4-page document, about what you do, what you want to do, what you needed money for. And all of that. So that was really time-consuming. Two hours, at least, just typing it up.

And we didn’t get it. They just said “we’ve received so many applications” – it was just a stock email.

And then there was the Women’s Centre, for one of their funding applications. That one was a [shorter] form, so it was quite easy. Again, we didn’t get it.

For in-person meetings pre-covid, the group used a room at a wheelchair-accessible arts centre / cinema, nominally for free – but it wasn’t exactly free in reality.

We would have our meetings at Broadway. They did give us a room for free, and it was a quiet room, so that was really great.

But there was pressure to buy food and drink. Not every single person [had to], but at least some members of the group.

Apart from venue hire, there were other things for which money would make a difference, a key one being organiser time.

[During the “lockdown” stage of the covid pandemic] I thought a zine would be a nice way to do something together, from a distance, and then people would get to have it, and see it.

But it was difficult to organise, and… yeah. It didn’t happen. None of us get paid, and because we were all so busy with other stuff…

The Manchester and Birmingham QPoC groups have each done more than QTIPoC Notts. Tuk reckoned that a key reason was that those cities each have physical LGBT centres, which Nottingham doesn’t. This means those groups each have an easy-to-organise, free or cheap place to meet. Comparing with Birmingham:

They would get that space for free, as well. So they were able to organise big events. Not just meetings, but I remember they did a big creativity day with loads of workshops – a weekend, actually.

But yeah I feel like it’s difficult in Nottingham, because it’s difficult to find good spaces.

There are lovely spaces in Nottingham city centre – but they’re more expensive than a grass-roots group would typically be able to hire. For example, there are better rooms at Broadway:

They sometimes do small screenings, or after a film, they’ll do a little panel discussion, in those rooms. You just sit around on sofas and that’s such a nice environment. [But these rooms are more expensive per evening.] I think it was definitely over £100, maybe over £200.

Case Study: Leeds Bi Group

Leeds Bi Group is a great example of the difference it can make to have support from, and partnerships with, other local organisations: for example, some excellent collaborations with Leeds City Council.

It’s also in the relatively unusual category of “grass-roots local groups which got as far as setting up a bank account“.

Quotes in this section are from Emily, who founded the group in 2014.

The reason I set up Leeds Bi Group was ’cause I was sat there like “Am I seriously the only bisexual person in Leeds? Where are they? Why is there no community for me? I’ve just realised I’m bi, I wanna do something about it”.

I saw Edinburgh [start a group], off the back of the BiCon in Edinburgh. And next year [BiCon] was in Leeds, so I was like well, this is a perfect opportunity. I will engage with the community. I’ll do a little focus group, as a workshop, and see if people want this.

People did. And it grew from there.

Early “getting started” money came from within the community.

We got something like a hundred pounds from BiCon Continuity, back in the day when we first started up, to pay for things like flyers.

Their first meeting space was at Yorkshire MESMAC, a charity.

They have a building in Leeds, and they gave us space for free.

I could have my post delivered there. I do have my [home] address on my bank account stuff because you kind of have to. But everything else is under MESMAC’s name, with a “care of” thing on.

Links with the council and other organisations built up gradually.

I was involved in starting the first IDAHoBiT event in Leeds. It was me, it was some people from the Council, and it was some people from one of the universities.

And from that kind of work, we kind of all came together and said: OK, what’s Leeds gonna do for Bi Visibility Day. And it’s from them, with them saying “we can give you some money. If you want some money, we can give you some money, and make it happen” that the links were made.

Unlike many small groups, they had a bank account from early on.

My sister worked at a bank at the time, so I could go to her and go “I don’t understand what I’m doing! Help!” And then “the bank’s doing weird things, what do I do?” also.

It’s things like: go to the bank that is your own personal bank, because if they already know your details, it makes the process smoother. Which has been fine for me, but hard to get other people on [as signatories], because no-one banks at the same banks that I use.

[For a constitution] – we nicked it from another group. With their permission.

Even with a bank account, it can still be tricky to navigate making payments.

If you’ve got two joint signatories, but you need to pay for something that you can’t be invoiced for, that is a difficulty that no-one really tells you about. I have to pay for everything, and then charge it back to the bank account. It’s annoying, and I’m lucky that I’m in full time employment, and have the ability to pay £200 on my credit card and then quickly get the money back from our bank account – as long as we’ve got a treasurer in place.

[Another difficulty is] you have a bank account, with two signatories, and you have a PayPal account. You can’t link the two, because PayPal won’t link to an account that doesn’t have a card, and a joint signatory account won’t have a card on.

Like many groups, they’d had difficulty at times over changing the bank signatories.

I was trying to get one [signatory] off our treasury books, and somebody else new on. And they [the bank] messed it up, and it took like nine months to do.

And then the same thing happened again, where that treasurer left suddenly, and we needed someone new on. And trying to get that paperwork done, again, took about six months.

Money came in via various small funds, and from the community via events.

[For events, especially any with food,] we didn’t want people booking the tickets and then not going. So sometimes we put a price on just to make sure that people came.

If you’re a City Councillor in Leeds, you have a little pocket of money, that you can then spend on things supporting the community.

We’ve done a couple of charity pot parties with Lush. We go into one of the Lush stores over the weekend, and they give us all the profits from the charity pots from that store for the weekend.

Events meant hiring venues.

We have also been quite lucky to get good rates at generally queer-friendly venues. A lot of bi group expenses went on venue hire.

It’s been really nice running things virtually, and not having to put money into people’s travel costs and venue hire.

The group didn’t necessarily want to accept all the funding which was offered to them, because of the implications in terms of ethics and inclusion.

Is it appropriate to the events that we’re running. Maybe you’ve got an alcohol logo on it when you’re offering dry spaces. And things like that.

The group began decorating bags and making badges to sell: initially not really to make money, but to create more visibility for bi people.

We went to BiCon Continuity again and we said we’d like some seed money, to make some of our own merchandise. We want to paint some tote bags with bi flags, and we wanna make some badges, and we wanna sell them. For next to nothing, but we just think that there’s not enough bi+ merch out there, so we want to do some stuff.

[The badges] got to the point where it was actually somewhat profit-making. So we would get more money selling badges than we spent making them, even with buying a badge maker and everything. [Though I don’t love it so much] when it’s half eleven at night, the night before the event, and you’re starting to get repetitive strain from moving the badge maker!

In getting funding from outside, the amount of admin varied a lot.

With the council, I only had to put a well-written email through to someone, explaining why this is something the council should support, and that’s been it. It might be because they know me, so I’ve already got the reputation with them.

With Lush, there was a form to fill in. It was along the lines of, you know, “what are your aims, do you have a website, what are your social media accounts, do you you fall within this bracket of income?”

Leeds Pride – we had to fill in quite an extensive form for Leeds Pride. There’s the one to march in the Pride, which is often quite difficult, and then there’s the one for the community grant.

We also went to the LGBT Consortium for some money for the Bi+ Allies Guide that we produced. And they printed it and did a launch event for us, which was very lovely. That was an extensive form to fill in: the biggest for the bi group.

None of the sums of money had been large:

It’s all been very small pockets of money: £250 here, £50 there. We’ve not ever been anywhere near “you have to apply for charity status now”, put it that way. It’s been a steady trickle in, and a steady trickle out again.

The biggest we got was for the Bi Allies’ Guide, because it was printing and website and other things. Might have been in the region of a grand, give or take.

As well as the time filling in the forms, a lot of mental energy went into working out what best to ask for.

[For the Bi Allies Guide] We said, OK, so we want a physical published copy, but [also] we want to be able to put a copy of this online, and at the moment our website won’t let us do that. [Money for the website] will support us getting the Bi Allies Guide out there.

So we got our website and two years’ funding, [as part of] the Bi Allies Guide.

And we would go to Leeds Pride and say, we want to put on a pre-Pride-march brunch, and we’re gonna have some face painting, and we’re gonna have some balloons that are our decorations, and things like that.

The pretty decorations could be taken [with us to the march], and suddenly we’re at a Pride march with a load of purple balloons, and things like that.

It was truthful, but it also meant we benefitted outside that specific event, or thing we were planning for.

At the time we interviewed Emily, the group was in the process of winding up after 7 years, and a new group was in the process of forming. Emily had thoughts on what else the group could have done, with more time and money.

People need to learn more about us still, ’cause it’s still so erased and underrepresented. And I think that’s where the work needs to be done. All those people who aren’t out. And like, me at 20 not knowing that I was bisexual because I liked guys, so I must be straight.

I work full time, Monday to Friday, and sometimes I’ve thought maybe if we could get enough funding in, hire me to work one day a week, so I can drop my regular job down to four days a week. Then we could do this amazing work in Leeds, wouldn’t that be great.

Working more with the council, to embed stuff within them. The local NHS trust. Potentially schools and things like that, yeah.

I think potentially, more publications, more engagement work. Bigger things like Bi Visibility Day, a wider bi+ presence within pride, and things like that, just making it more embedded into the whole city.

Many of the themes which run through Tuk’s and Emily’s accounts were reflected too when we asked other bi organisers what they’d do if they had some money. Three very common themes were outreach, access and paying people.

Of course, any group may want to reach new members, but there are bi‑specific factors too. Bi organisers are acutely aware of how erased into invisibility we are in the wider world, and how many people haven’t yet found a bi community. Many of us spent a long time not knowing any other bi people. Many of us took a long time to recognise ourselves as bi, because bi people weren’t visible as ordinary real people in our world, only as stereotypes.

In part because of the cultural invisibility, there are people who’d never think to look for a bi group – we have to show them we exist.

How would money help?

Almost everyone who was asked about money mentioned flyers.

→ particularly [to reach] older people who are more likely to be digitally excluded.

Other resources mentioned were posters, booklets, and hiring or insuring stalls at Pride.

When we asked what a paid worker could do to help a group, very often that too came under the heading of outreach or publicity:

→ If we did have a one day a week sessional worker, I would want them to do a proper scoping exercise about how to find older bi people who are not part of the LGBTQ community. Whether it’s worth going into day centres putting out posters trying to reach people – because we know they exist – some people really marginalised and not connected at all.

→ [If we had paid admin help] We could easily have a monthly bulletin. That could be going out to every student union LGBT soc and every signed-up local LGBT network, or Meetup group, in the country.

Because many organisers are either disabled or working a full-time job, some were struggling for time or energy even to keep the group’s web site updated:

→ I want help with publicity as well. I’ve not updated the web page in years. I just don’t have the time. I’m mostly reliant on email and Facebook to run the group at the moment, and I’m conscious that won’t capture everyone. The web site is public-facing.

Organisers are usually very aware of the needs of new people who might visit, and that shows in how we think about spreading the word.

→ When they’re new, the biggest hurdle is coming down the first time. It’s partly that you might not be out. It’s also just partly that a lot of people have anxiety about going into new groups at all. Even if it was a craft group or something.

→ People are nervous if they haven’t seen other people’s comments, or been before, and seen how it works. They think maybe it’s a sex thing. Or that they’re going to be hit on all the time. And so I try and [keep on] explicitly saying everywhere “we’re not a hook-up group, yes people may date, that’s not our focus”.

I’ve wanted to do a YouTube video for new members – “this is what it’s like, come and watch an event, just see what the atmosphere is like.”

6.2 Money for access, money for venues

A lot of bi people are disabled. Some are parents or carers. Some are autistic or otherwise neurodivergent. Deaf and hard-of-hearing bi people have been central within BiCon organising. A lot of trans people and nonbinary people consider themselves “under the bi umbrella”. And bi people are disproportionately likely to be living on low incomes.

Another factor for all LGBT+ groups is of course outness. Some people feel most comfortable in an LGBT centre or known gay-friendly pub, to minimise the risk of bother. But if there are people in your life you can’t afford to be out to, those are the most scary places to be, in case you’re seen there, or seen going in.

All of this makes access of various kinds a central issue to bi organising, both in person and online.

→ Thinking of access and how things are paid for formally or informally (such as feeling obliged to buy drinks) and also travel costs, not being on public transport [routes], childcare etc.

In our survey, when asked about venues, every local group ticked either “A pub or other licensed venue, which we get for free”, or “Another venue we get for free”. A few also used paid-for venues at times.

→ My advice for running a group: “Accessible venue“. But that’s like the Holy Grail, isn’t it.

→ For people with physical disabilities, places that are hard to reach (are they near public transport, do they require a lot of walking, do you have to go up stairs etc), does it require a lot of standing, that sort of thing.

Then for neurodivergent people, places that have a loud atmosphere or too much sensory overload.

→ We meet in a pub in [city] that has a long reputation of being LGBT+ safe space. So from that point of view it’s a good place to meet.

But one thing I didn’t realise till I was talking to a wheelchair user, is it’s not really wheelchair accessible. I had thought, “well it’s got step-free access, so all good”.

The choice of pubs or bars, or the presence of alcohol, were mentioned a few times as access issues.

→ Groups that meet up in bars are hard for a lot of people.

→ It’s normally okay [in the pub], but occasionally we get this big group of football lads who come after a game. They make so much noise. It’s really disruptive when you’re trying to have a quiet social.

Although bi organisers are extremely good at scoping out the best compromise of a free/cheap venue, there’s no doubt that money would make a difference:

→ Our local Friends’ Meeting House, that’s absolutely gorgeous. But their rates are beyond the group’s pocket, normally. We have been there occasionally.

I think this does loop back to the, you know, “we all expect to be skint, all the time, so £3,000 seems like a lot of money”. And it actually isn’t. If you’re hiring an accessible venue once a month, that’s gone in a few years.

→ In London, a hundred pounds “doesn’t touch the sides”, does it.

Several groups were able to use a venue via their connection with another organisation.

→ Bi The Way is a group run by Opening Doors London.

→ Bi and Beyond get their room for free from LGBT Health, for instance. And then LGBT Health report to their funders to say “we are supporting the bi community in this way”.

What about online spaces?

As the covid pandemic pushed events online, new skills and resources were needed:

→ I’m very good at holding the space in person but virtually it was a bit different.

→ Funding for closed captioning to make the Zooms more accessible.

The virtual meetups had advantages too, for connecting people who wouldn’t have met at the in-person groups:

→ [The way things have moved online] has really opened things up for disabled people like me, who often have difficulty travelling and accessing live events locally.

As so many bi people are disabled and/or on low incomes, financial access is a well-known issue. A lot of community-run events operate on a sliding scale. London BiFest gives free entry to people of colour. BiCon has the “Helping Hand fund“.

Organisers also had other ideas:

→ We’d really like to be able to fund for low income people to come to events in a shame free way. Maybe having a gift card with funds on it that people who can’t afford a meal (which we buy in return for the space) could buy food on.

→ Funding for some data, for people who don’t have unlimited data plans.

→ Travel costs. Free tickets for POC and those in extraordinary circumstances.

As with outreach, access came up when people thought about the possibilities from having a paid worker:

→ a lot of our spare funds we have now are spent on inclusion, so it would be great to continue that with someone in charge.

UK bi networks already hold an enormous amount of skill and experience – which doesn’t necessarily get transmitted around efficiently, partly because the people holding it are limited by energy or time.

Here’s Marcus Morgan, director of the Bisexual Index:

What I would love to be able to do is more mentoring, more training, and more teaching, of the things that I’ve – I’ve not been taught, but I’ve come to learn, over 30 years. Not just about bisexuality, but about how to be an activist: how to approach organisations when you need to talk to them, and how to teach people about bisexuality… that I really want to try and pass on, to future activists.

I want someone to say: We are an organisation that mentors and trains LGBT people to support other LGBT people; we’d like to sponsor an event like that, but for bi. I want activists mentoring activists. And I want it to be funded, and I want some of the funding to pay people to be there.

In one of our research discussions for organisers, we asked about situations where they wished they could have asked for advice.

Several people mentioned emotional skills, self-care and knowing where to draw boundaries, when difficult situations come up while you’re in a hosting role.

→ There have been situations where people have come who have brought a lot of stress about their situations to a meeting and I’ve been [hosting] on my own. It’s not a counselling group.

→ Anything that is risky legally, anything that is risky emotionally – particularly around unpaid emotional labour and safeguarding.

→ The sticky emotional moments. It’s really difficult sometimes to separate yourself from the stories you hear, and the people in the community that are struggling, and you can’t always help. So for us, if we had finance or time to get some training or support for volunteers, that would be amazing.

And then of course there’s all the potential learning around funding, charities, constitutions, bank accounts and so on.

→ It’s not really about filling in a form. It’s about familiarity with a structure of how things work and what things cost.

→ [Making people realise] how far it can go to give someone ten pounds towards their internet costs to participate. How much difference to somebody’s life that can make.

→ Concepts that need to be covered. One is full cost recovery: what are your actual costs, and how they get covered. The other point is results based accountability. What do we mean by outcomes?

We’re all making a difference to communities, we’re making outcomes. But only people who are working in the sector in our day jobs would be able to write down “these are the outcomes”.

We know that people in the community can understand that and do that well – they just have never been taught.

Training has to match the stage of the problems which the group and organiser are dealing with:

→ “Take along your founding articles and constitution, and your list of trustees, and…” The assumption that those steps are easy… grates on me.

→ I’ve been on so many different training days. It’s like oh, “double check”, “read the guidance twice”. I already read the guidance, like that’s just not an issue I’m having! “Make sure you state this clearly”.

I don’t know what to say is what I find difficult until I have the form in front of me going “I don’t know what you want from this answer!”

But the money training must be targeted for the people who actually do need and want it:

→ Obviously [money training] is good and it should be available, but I also worry that it’s a bit like “now every bi group runner has to learn to fundraise, and then fundraise” – and they don’t have time, which is another part of the problem.

Another organiser echoed Marcus’s point about transmitting the wealth of skills we already have:

→ Giving development support to organisations and groups: we can’t just arrange all of that ourselves to pass on our knowledge, because we are too busy doing the work. But if we had support to do that, that could go a long way.

6.4 Money for running events

Annual gathering BiCon in particular has been an enormous time commitment for the main organisers, provoking discussion about both the ethics and the practicalities of paying people.

→ I do think people that run things like BiCon should get some sort of money, ’cause it is an awful lot of time to take out of schedules to actually run a BiCon. Or even a BiFest.

→ Not relying on unpaid labour in general would be good.

→ I don’t think you can pay someone less than [national living wage]. I don’t think that would be ethical. At that point, you might as well be a volunteer.

→ [From a BiCon organiser] When I added up the hours it involved, it got scary. You can’t pay [national living wage] if you are spending 1,000 hours, without finding £9,000 from somewhere.

→ A lot of people in the bi activism community have the luxury to volunteer because they have well paying jobs in the first place, which is not true for all of us.

Most organisers didn’t raise the idea of being paid to run their regular meetups. But some did want to be able to call on deputy hosts for when they have to miss a session.

→ Some support would be nice, the odd time I can’t manage a social, or I barely have the energy have to drag myself, because there’s no one else that can run them in my absence.

→ [From a disabled organiser] Somebody to turn up if I can’t turn up. Virtual meetings have been good for me, because if I’ve been too ill to get out, I can still do virtual.

We heard of an example where a local LGBT organisation, which lets the group have a room for free, had occasionally given support with facilitation. This enabled the group to benefit from staff time without hiring anyone directly.

There were other ways that a co-organiser (paid or unpaid) would be able to help:

→ I think in some ways time would be more useful to my group than money. I would be thrilled if somebody turned up and said [they would help]. I would first of all suggest that they co-host the group, which is what we’re looking for at the moment. [If they had more time after that] Finding speakers, activities, doing all the research background stuff that I’ve been doing.

A great many resources (like literature and web sites) would come under the heading of “outreach”. But there can also be practical things needed to run the actual events.

One recurring theme was technology.

→ Upgrade to Meetup Pro subscription, to integrate with other services better.

→ [For educational presentations] Hiring sound equipment. Or, you know, the room we’ve found doesn’t have a projector. OK, well, let’s hire a projector.

A couple of people mentioned that they were currently paying for food for their meetups:

→ The thing that I was paying out of pocket for was refreshments. I could easily do a hundred pounds on crisps in a year.

→ [If we had more money:] Provide food and drink so that people wouldn’t have to bring their own.

7. Ways to get money to groups, in practice

Two case studies follow, which we think are useful practical precedents for the distribution of money to grass-roots groups.

The first is from 2020-2021: the Equality Network‘s distribution of covid-related funds from the Scottish Government.

The second is the Bisexuals Action for Sexual Health Peer Education Project (BASH PEP), a community-led enterprise from the 1990s, which had funding from Red Hot AIDS Charitable Trust.

Case Study: Equality Network Covid Funds

Equality Network is a charity “working for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex (LGBTI) equality and human rights in Scotland”. In 2020-2021, they got £53,500 as part of the Scottish Government’s covid emergency money, for LGBTI community support. In all, 64 groups received money.

This summary is based on an interview with Scott Cuthbertson, Development Manager at the Equality Network, who took the lead on organising the process.

For the groups, the application process was a fairly informal meeting, usually with Scott. In most cases, he already knew the group. If not, a colleague did, or at least they were visible online.

We had the same chat with everyone. It was usually a Zoom meeting. It would usually last between 20 minutes and half an hour.

Scott created a form to track the process with each group, and be the basis of the payment authorisations.

It explains who the groups are, what the contact is, what challenges they face during covid, and where the money is going. Quite simple – I could fill it out in minutes. And I fill that out for the group.

Groups varied enormously in how much money they asked for.

Some groups wanted fifty pounds, some groups wanted a thousand pounds, some groups got a little bit more, depending on their need, and what they’re trying to achieve.

The report back to the government needed to include the number of people reached, which groups had had the money, and in general terms, what for. In terms of accounting, the key thing was that each group must provide receipts.

An important challenge to meet was the logistics of funding groups who’d never received funding before.

Off the top of my head, I’d say there was probably about a fifth of groups that didn’t have a group bank account, and we paid them to personal accounts.

The key element for me there was: we required a receipt. And it didn’t matter to me whether that receipt was from your own bank account or from a group bank account.

Some volunteers couldn’t risk receiving any group money into their own account, in case it caused problems with their benefits.

It was sometimes a case of asking, well do you have a partner, or a parent who has a bank account, or is there someone that you know that could potentially act as a bank account for this money. We need the receipt, and… That’s how we got round it.

For four of the groups, the only way they could find was for the group volunteers not to touch the money at all:

They didn’t know anyone in their group that wasn’t on Universal Credit, or had a bank account that they could access.

And so we bought [the resources the group needed], and paid for them. So we had all the receipts. And then we sent [the resources] to them. And that got round that issue.

Working in this flexible way of course meant a higher burden of admin at the funding end compared to “normal times”.

At the same time, the reduced admin burden at the groups’ end meant that many groups across Scotland received funding for the first time ever, making it an enormous success by that measure.

I am proud of how it worked, for sure. As a funding model going forward, I’d love for the funders to adopt it. I wish there was a pot of money I could just get my hands on and do that again, but… I don’t know that that’s going to happen.

Case Study: Bisexuals Action for Sexual Health

Bisexuals Action for Sexual Health (BASH) organised a Peer Education Project in 1995-1996, with £19,500 from the Red Hot AIDS Charitable Trust. A half-time Project Worker was funded for a year.

A paid worker would run a series of training events for the organisers of the local bisexual groups around the country, who would in turn run safer sex and other HIV prevention workshops for their groups.

The project included a plan to give grants of up to £100 to grass-roots bi groups where a group member had taken part. 15 of the 21 groups did claim.

The centrepiece training weekend took place in the November, after which the participants ran their sessions for peers.

If a group wanted to claim the £100 grant, they had to fill in a very brief application form, to say what they would do with the money. No-one was turned down.

In total £1457.60 was claimed.

The groups used the money in different ways:

Most peer educators who claimed money have used it to advertise, and buy resources for, their safer sex workshops and group. Some used it to fund specific events or projects. For example, the London Bisexual Group used it to advertise their 15th anniversary celebrations, Nottingham Bisexual Group for line rental for their new phone line … The representative of the London–based Bisexual Helpline used the project grant to attend the National Lesbian and Gay Phoneline Conference … .

The evaluation of the project named small groups in particular.

It has probably had more impact on smaller groups than those that are more established, such as the Edinburgh and London bisexual groups who have carried out more peer education previous to the project and who have more funds.

7.1 Possible structure: Participation as a natural measure of commitment

What can we learn from those two case studies?

An elegant aspect of the BASH PEP design was the way the participation of volunteers formed a natural measure of commitment. “If you’re committed enough to give up a weekend to do the training, then we trust that you’ll do good things with the money.”

This gives an opportunity to reduce the admin burden around writing and assessing application forms.

Also, there was no significant amount of gambling with time. Volunteers didn’t have to do the brief application form till part way through the project, and they knew they were likely to get the money.

The BASH PEP structure wouldn’t have worked if the training on offer hadn’t been considered valuable in its own right by group members. The weekend of training didn’t feel like a tedious hoop to jump through just to get the money; the people who stepped up for it wanted to learn about safer sex and workshop running.

This model could be adapted for other situations. For example, a year’s funding for hire of an accessible venue could be unlocked by a certain level of participation in training to facilitate a group.

7.2 Possible structure: Informal interviews as applications

It’s clear that for the Equality Network community support funding, informal interviews worked well as a method of taking applications. This possibility came up in other discussions too.

The time taken is likely to be shorter than filling in a form. But the main advantage people brought up was how much less daunting and more accessible it would be in terms of understanding what’s been asked.

→ Obviously, because you’re talking, it’s more accessible in that way. Somebody’s asking you questions, rather than a vague prompt, or statement, that you then have to try and figure out what’s relevant, and what’s gonna get you the funding.

→ You’re talking to a person instead of talking to a blank form.

→ No bi groups in the UK have professional bid writers. Generally a more simple and straightforward process for bidding would ensure a broader range of bi groups would be able to apply. This is also an accessibility issue.

Even if you did still have to fill in a form, it would help to have someone from the funding end to talk you through it:

→ So I think maybe some kind of consultation process, that’s probably more work than they’d be able to put in, but just being able to say if you’re struggling with this form, contact us on here and we will sit and go through with you.

7.3 Possible structure: Catalogue method

A challenge well met by the Equality Network setup was how to get resources to groups who aren’t currently equipped to manage money. But in that example, there was a question mark over the sustainability of the admin burden at the funding end, due in part to the complexity of so many different situations and requests.

The resources wanted by a small bi group often fall into predictable patterns. For example, a common wish is for paper flyers with the group’s details and meeting dates.

A volunteer panel could agree a catalogue of resources which any bi organiser could request, such as flyer design and printing, books to lend to group members, or flags for event participation.

A worker based within an existing organisation could be funded for a certain number of hours per week to manage the admin: taking requests, posting physical resources, and managing orders (e.g. to get flyers printed).

The recipient groups would never need to account for money, since they would never touch the money themselves; however, they could be asked to report briefly on results, e.g. numbers reached.

8. Ring-fenced funds and a virtual bi centre

During our research process, there was some discussion of perhaps setting up a new independent bi organisation, e.g. a new charity, with a focus on supporting grassroots bi groups. But the idea of the “virtual bi centre” was seen as more efficient:

→ By purely existing and being intermediary, anything that takes you one step removed creates in itself costs and complications. If it’s about [distributing] small amounts of money, that would just create an unnecessary level of burden. [You don’t want to] end up with a tiny amount of money to actually do projects.

→ If we had a virtual bi centre which had a paid admin, say. You could say “this project is based at this virtual bi centre” – which would have to have a physical address, but it wouldn’t have to be a building people could come to. There’s lots of things that could be done a bit more centrally.

→ Not the small local bits, not the big, big events – but actually the intermediary [level], where groups want to work together or do something across the UK and pool our resources. Those kind of research projects, shared resources –

When it comes to wanting to do things together [across groups], then having that kind of organisation as a coordinator and a central point would be quite useful.

There was precedent for having a bi panel to set the agenda and approve spending:

→ Wales Council for Voluntary Action – which is the Welsh equivalent of National Council for Voluntary Organisations, NCVO: When they’re doing youth grants, they have a panel of young people decide. They don’t have “a panel of their staff who happen to be young”, they don’t have “oh, we have 50% young people on the panel”: they have a youth panel to decide youth grants. We should have a bi panel to decide bi grants.

Table of Contents

Bi Funding Research: Funders’ Briefing

Key points

1.1 Bisexuality background

1.2 UK bi communities in 2021

2. Key obstacles “in between” bi people and existing funding

3. Recommendations

4.1 Why bi spaces are important, even when LGB/LGBT spaces exist

4.2 Where bi people go, other than bi groups

4.3 What’s typical at a grass-roots bi group

5. Applying, or not applying, for funding

5.1 Time, energy, the admin burden, and getting nothing back

5.2 Misfitting with what’s on offer

5.3 Not knowing where, not knowing how

5.4 Anti-bi prejudice in the sector

5.5 Dipping into the community’s pockets

5.6 The tradition of creatively “making do”

Case Study: QTIPoC Notts

Case Study: Leeds Bi Group

6. What money could do

6.1 Money for outreach

6.2 Money for access, money for venues

6.3 Money for training

6.4 Money for running events

6.5 Money for resources

7. Ways to get money to groups, in practice

Case Study: Equality Network Covid Funds

Case Study: Bisexuals Action for Sexual Health

7.1 Possible structure: Participation as a natural measure of commitment

7.2 Possible structure: Informal interviews as applications

7.3 Possible structure: Catalogue method

8. Ring-fenced funds and a virtual bi centre

Note: click here for the other documents from the bi funding research, and PDF copies to download.